The Louisa Anne Meredith Medal and The Peter Smith Medal

The Louisa Anne Meredith Medal is awarded every four years to a person who excels in the field of arts or humanities or both, with outstanding contributions evidenced by creative outputs. The medal honours Louisa Anne Meredith’s contributions to the areas of natural history art, scientific art, literature, history and to The Royal Society of Tasmania. The medal will be awarded in 2024 for the first time having been established by the Society in August 2023.

The awardee receives a medal and will be invited to deliver the “Louisa Anne Meredith Lecture”.

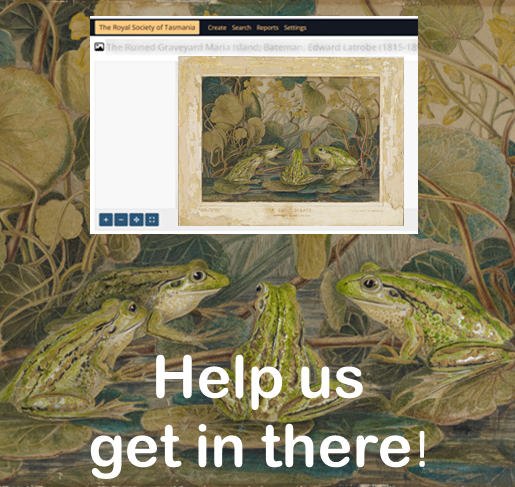

Louisa Anne Meredith (née Twamley) was a remarkable woman, a prolific artist, writer and social commentator. She was the first woman to be granted Honorary membership of The Royal Society of Tasmania in 1881. The RST has a large number of her sketches and watercolours in its Art Collection, as well as a number of her books in its Library.

Meredith contributed a great deal to the work of The Royal Society of Tasmania. Over several decades, she sent interesting specimens to the Royal Society Museum and presented beautiful and accurate watercolours of many specimens to the RST. These artworks were much admired at Society meetings as being ‘beautifully executed’. The Royal Society of Tasmania also purchased a number of her illustrations at the time.

Further details and nomination guidelines for the Louisa Anne Meredith medal are at this link.

The Peter Smith Medal is awarded biennially to an outstanding early career researcher in any field. The awardee receives a medal and will be invited to deliver “The Peter Smith Lecture” to the Society.

For the purpose of the medal, “early career” means within the first seven years since the award of a PhD, at the time of the nomination deadline. Extensions to the seven years post-PhD eligibility requirement will be offered to applicants whose career has been interrupted to accommodate carer responsibilities, illness or other circumstances.