Stories from the Royal Society of Tasmania Art Collection

4. An interesting collaboration

Article prepared by the RST Honorary Curator, Dr Anita Hansen, for the May 2022 RST Newsletter.

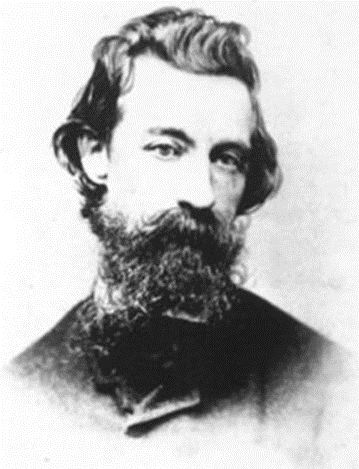

Edward La Trobe Bateman (1815?–1897)

There is only one sketch by Edward La Trobe Bateman, an exquisite pencil drawing with white highlights, in the Art Collection of the Royal Society of Tasmania. There is no record of how it came to be in the collection, only that it was on the Loans List in 1965. I have an idea about this which I will explain later.

Despite being represented by only one sketch, Bateman had a far greater impact on the collection than would be imagined from this one example.

Unknown photographer, 1870s.

The sketch is of Maria Island. On the drawing he has inscribed, ‘The ruined graveyard on Maria Island on the East Coast of Tasmania, where the prisoners and their keepers who died there were interred while it was a convict station.’

‘Maria Island operated as a penal station between 1825 and 1832 – The settlement, which was located at Darlington, was conceived as a half-way house between the extreme of hard labour at Macquarie Harbour and a stint in a road or chain gang. Convicts sent to Maria Island worked in a number of different industries including timber-cutting, tanning, shoe-making and cloth production. Plagued by frequent escape and other disciplinary problems, Maria Island was closed and much of the remaining convict population relocated to Port Arthur in 1832.After being abandoned for ten years, the site was reopened in 1842 as a probation station. A second station was constructed in 1845 at Point Lesueur. Convicts at both were primarily engaged in agricultural work. Overcrowding remained a constant problem, however, and both stations were closed in 1850. Following its abandonment as a convict station, the island was used to run sheep.’ – Companion to Tasmanian History, University of Tasmania.

The sketch was drawn sometime in 1859, so it is somewhat surprising to see the graveyard in such a state of disrepair considering that the convict stations had been closed for fewer than ten years at that time. The fence has collapsed leaving the graveyard open to the grazing sheep relaxing in the foreground. In other places the graveyard has become overgrown with scrubs.

The sketch shows the work of an accomplished artist. In England Bateman had worked with Owen Jones, who according to the Australian Dictionary of Biography, ‘produced from 1841 the first and finest chromolithographic books issued in England. Two at least of his ‘illuminated’ gift books, Fruits from Garden and Field (1850) and Winged Thoughts (1851), were chromolithographed by Bateman with flowers and birds to accompany poems by Mary Ann Bacon.’ This experience would prove to be noteworthy later when he came to Australia.

In 1852, Bateman and friends set off for the goldfields in Victoria. At the goldfields Bateman seemed more interested in sketching the scenery around him than in prospecting for gold. It was noted by one of his companions, William Howitt that, ‘he will paint all the flowers’; at the McIvor diggings in 1854 he ‘was besieged … to sketch tents, huts or stores … and netted a considerable sum at £5 per sketch, a small pencil one at that’. In truth, this was arguably more profitable for him than digging for gold.

An Interesting Collaboration

In Victoria, Bateman stayed with a relative of his prospecting companion William Howitt – Dr Geoffrey Howitt – at Collins Street and at his house at Cape Schanck.

It was here that he met Louisa Anne Meredith and her family when they visited Victoria in 1856.

There is a delightful pencil sketch of Cape Schanck by Louisa Anne Meredith in the RST Art Collection.

In 1859 Bateman came to Tasmania and stayed with Charles and Louisa Anne Meredith. It must have been at this time that he made the sketch at Maria Island. It was also at this time that he began collaborating with Louisa on her latest book Some of My Bush Friends in Tasmania.

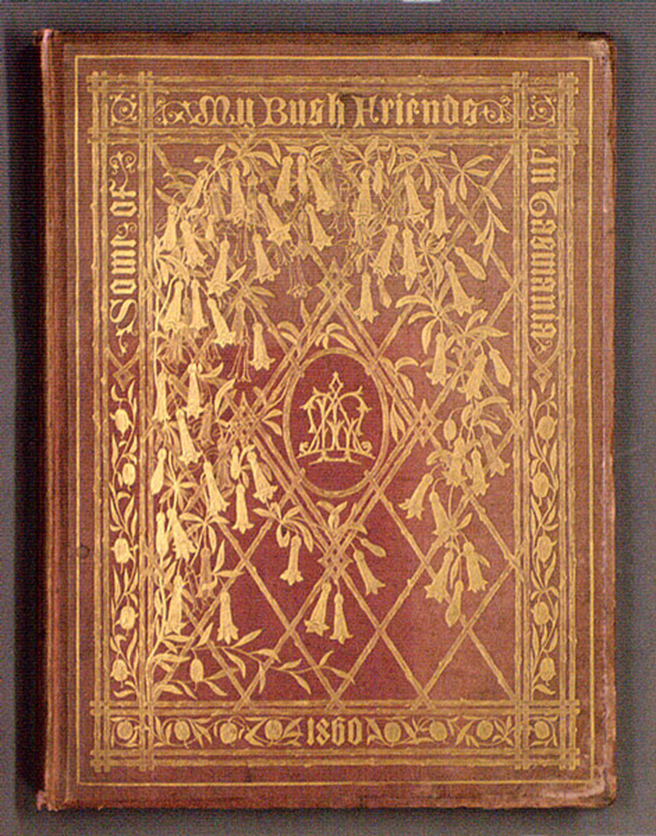

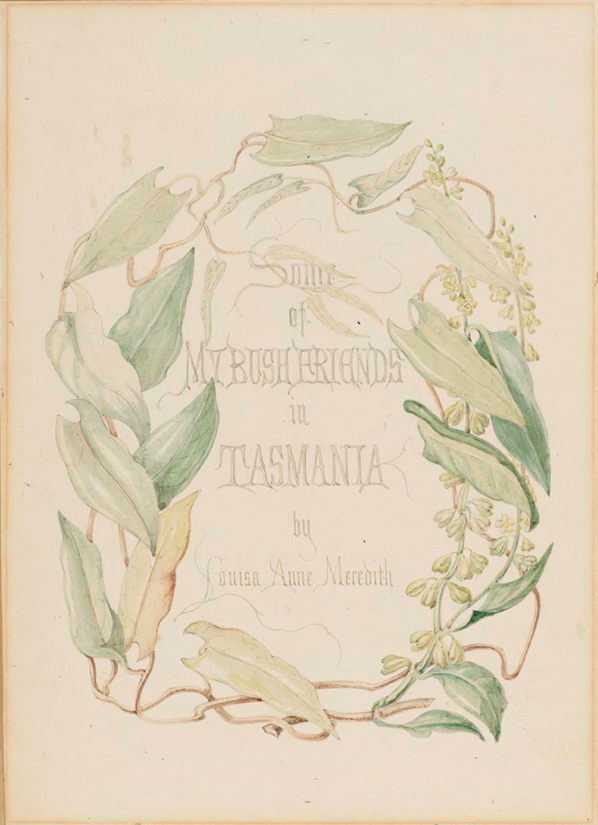

Bateman is best remembered for his contributions to book design. His initial headings, tailpieces and titles engraved on wood by Samuel Calvert for several catalogues issued by the Melbourne Public Library from 1861 were the first instances of Australian flora being used for decorative motifs. The two volumes of Louisa Ann Meredith’s book, Some of My Bush Friends in Tasmania, 1860 and 1891, which scarcely differ from the Owen Jones gift books, each contain Bateman’s ‘quaint lettering’ in their poem-titles and display his designs on their embossed covers (Australian Dictionary of Biography).

This work has been described as an ‘Impressive volume with stunning full page chromolithographic botanical plates of native Tasmanian flowers, in an embossed presentation leather binding. Natural history verse accompanied by illustrations, by an outstanding woman artist. The design of the book owes much to Owen Jones, the designer of the famed Grammar of Ornament and Edward La Trobe Bateman, who worked with Jones on various projects as illustrator and designer. Bateman collaborated with Meredith on both her books, providing lettering and edging details that are hallmarks of his work.’

As well as having the original watercolours for this book in the RST Art Collection, the Society has a copy of the 1860 volume in the RST Library at the University of Tasmania.

When Louisa Anne Meredith travelled to England to oversee the printing of Some of My Bush Friends in Tasmania in 1890, she again sought the collaboration with Bateman in her work, and Louisa and her granddaughter stayed with Bateman in Scotland during this time.

While Louisa and Bateman worked together in the production of the volume, it is interesting to note that they had very different ideas on how to depict the plants in the book. Louisa’s granddaughter reports, ‘ … L. A. Meredith would in her flower drawings put a leaf with a hole in it, or one an insect had eaten; and Bateman said that was not right, as you should only paint or draw perfect things.’

To finish – earlier I commented that I had an idea how the drawing by Edward La Trobe Bateman came to be in the RST Art Collection. I believe he must have given the sketch to Louisa when he stayed with the family in 1859, and it was most probably part of a folio of her work donated to the Society by D Meredith on 7 December 1945.

Aside

Chromolithography became the most successful of several methods of colour printing developed by the nineteenth century. Previously, a single outline was drawn onto a stone and after printing, each image was hand-coloured, very time consuming and expensive.

In chromolithography, several stones are prepared, each bearing a different colour ink. The print would be carefully placed in the same position, or registered, on the stone so the ink would go where intended.

Depending on the number of colours present, a chromolithograph could take months to produce, by very skilled workers. To make a reproduction print, once referred to as a chromo, a lithographer gradually created and corrected the many stones using proofs, to look as much as possible like the painting in front of him, sometimes using dozens of layers. Although this was time consuming, once the stones were correct, the coloured prints could be mass produced.

The Royal Society of Tasmania’s Art Collection is housed at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart.

Any queries, please contact the Honorary Curator, Dr Anita Hansen: anita.hansen@utas.edu.au